Risk Factors for ACL Injuries

ACL Injuries

You’ve likely seen ACL injuries happen, or you’ve heard about it: the dreaded audible “pop” followed by an athlete collapsing to the ground, clutching their knee. These are the tell-tale signs of an ACL tear that we see all too often in sports involving cutting, pivoting, and dynamic change in direction. Most ACL tears are non-contact injuries that occur during jumping, twisting, quickly stopping, or decelerating. The worst feeling is looking back and thinking, “Is there a way we could have prevented this?”

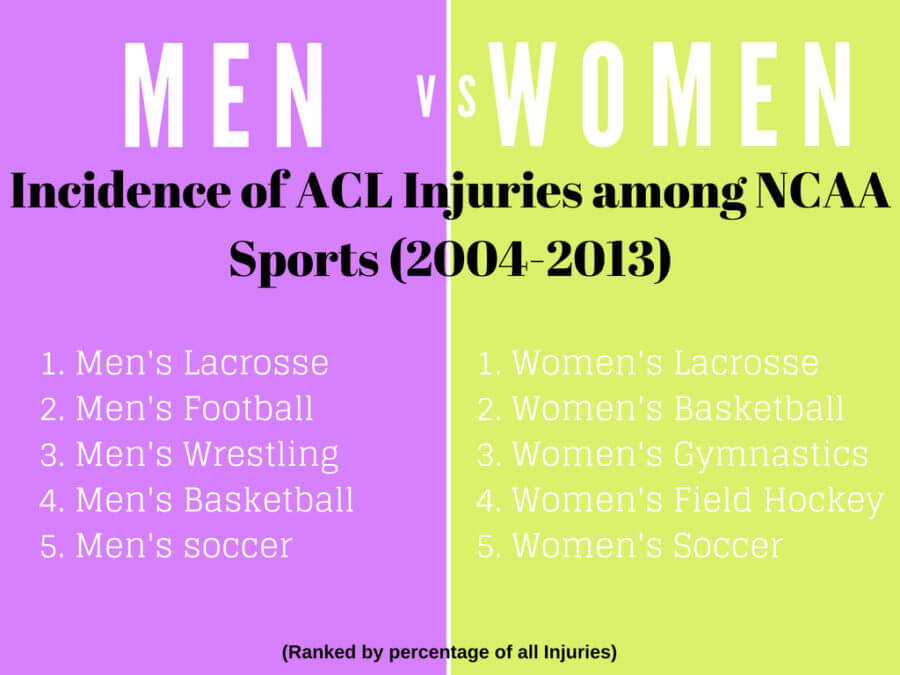

Despite the growing awareness of ACL injuries in the media, the prevalence of ACL injuries among youth athletes is on the rise. 1 out of every 29 female athletes and 1 out of every 50 male athletes end up rupturing their ACL during their athletic career (1).

Adapted from “Collegiate ACL Injury Rates Across 15 Sports: National Collegiate Athletic Association Injury Surveillance System Data Update 2004-2005 Through 2012-2013” (2).

Females have a higher relative risk for ACL injuries than males, but what makes them more at risk? There are certain inherent, or non-modifiable factors that put females more at risk for non-contact ACL injuries when compared to males. Biomechanical differences in female body structure involves wider hips (greater q-angle) and a narrower gap at the end of the femur (intercondylar notch) which leads to greater hip internal rotation and foot pronation, increasing the stress placed on the knee during high-level sporting activity.

Warning Signs

The good news is there are steps that athletes can take early on in their career to help prevent an ACL injury from occurring in the future. The first step towards ACL injury prevention is recognizing some of the warning signs. See below for what parents and coaches can look for as potential risk factors.

- Knees bending inwards during jumping, landing, and change in direction

- This can be a sign of weak hip muscles, in particular the gluteus medius which is responsible for hip stabilization and controlling inward collapse of the knee (knee valgus)

- The foot rolling inwards (over-pronation) during dynamic movements

- Indicates weakness of intrinsic foot muscles that help promote a stable arch and can affect stability up the chain to the knees and hips.

These compensations during movement are “warning signs” that often result in increased load or stress on the knees when an athlete is performing a change in direction movement with the foot firmly planted, which is the most common mechanism of injury for an ACL tear. Knee valgus and foot over-pronation are likely caused by muscular imbalances which can easily be addressed with a comprehensive and individualized injury prevention program. Such a program will include strengthening of the glutes and foot intrinsic musculature, training proper body mechanics, and teaching takeoff and landing techniques.

For more information check out our previous blog post to learn more about what an ACL prevention program should consist of. Feel free to contact us at The Fit Institute with any questions or concerns. Call us today to schedule a complimentary injury screen or to speak with a movement specialist. Our physical therapists and movement experts would love to answer any questions you may have! Additionally, former professional soccer player Jordan Angeli created the ACL Club, a support community for athletes going through ACL injury recovery. If you are having any physical, mental, and or emotional challneges due to the rigorous ACL recovery process this community will help give you the support you need.

Katie Budz – Doctor of Physical Therapy. Graduate of Rosalind Franklin University of Medicine and Science. Former collegiate athlete playing 4 years of Division III basketball at Dominican University in Chicago.

The FIT Institute is a physical therapy and sports performance facility in North Center. We increase the of an athlete’s career by teaching proper movement patterns that often lead to overuse injuries, we do this by bridging the gap between physical therapy and sports performance.

References:

- Montalvo A, Schneider D, Myer G, et al. “What’s my risk of sustaining an ACL injury while playing sports?” A systematic review with meta-analysis. British Journal Of Sports Medicine [/fusion_builder_column][fusion_builder_column type=”1_1″ background_position=”left top” background_color=”” border_size=”” border_color=”” border_style=”solid” spacing=”yes” background_image=”” background_repeat=”no-repeat” padding=”” margin_top=”0px” margin_bottom=”0px” class=”” id=”” animation_type=”” animation_speed=”0.3″ animation_direction=”left” hide_on_mobile=”no” center_content=”no” min_height=”none”][serial online]. March 7, 2018.

- Agel J, Rockwood T, Klossner D. Collegiate ACL Injury Rates Across 15 Sports: National Collegiate Athletic Association Injury Surveillance System Data Update (2004-2005 Through 2012-2013). Clinical Journal Of Sport Medicine: Official Journal Of The Canadian Academy Of Sport Medicine [serial online]. November 2016;26(6):518-523.